Suite au scandale des écoutes téléphoniques, le Premier Ministre David Cameron s’était engagé à mettre en place un nouveau système de régulation de la presse. Dans ce but, le juge Leveson a été chargé de rendre un rapport proposant des solutions afin d’éviter de nouvelles dérives. Cependant, dès sa parution, David Cameron a refusé l’application des mesures conseillées par le rapport. Pourquoi cette décision hâtive ?

***

Why a report about the regulation of the press?

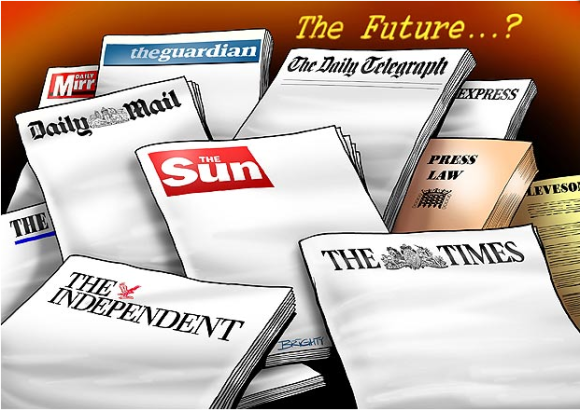

The Leveson inquiry released on the 29 of November is unambiguous: even though the press is an important safeguard of democracy, Fleet Street recently exceeded acceptable limits and the question that arises is, as Leveson himself puts it: « Who guards the guardians? ». After the dramatic and revolting cases of the little Milly Dowler and the phone tapping of relatives from deceased British soldiers, the entire Kingdom was waiting for a measure to prevent that situation from ever happening again. The methods used by some newspapers, as for instance phone hacking, would have been strongly criticized by the same media if used by any private firm or state. Therefore, an editorial code of best practice seems more than ever required, even according to some journalists who believe such cases tarnish the image of the whole press. Regulation promoted by the Leveson inquiry is not a new idea; indeed, the Press Complaint Commission was created in 1953 to maintain standards of ethics in journalism. Nevertheless, this voluntary press organisation disappointed by failing to meet its goal to protect individual privacy. Therefore, a large number of press editors, convinced by Leveson’s suggestions, already decided to apply most of them.

Why did the inquiry create a controversy ?

The Leveson inquiry proposes the creation of an independent body which would have more power to investigate illegal behaviours and which could levy fines. The first issue is that this new body has to be overseen by Ofcom, according to the report. But ministers themselves appoint Ofcom’s members, so this would be direct government supervision over the press, which could threaten the freedom of speech.

Secondly, Cameron and most newspapers and tabloids disapprove of a regulation law because it would be like taking a big step backwards before 1695 and the end of the “ licensing of the Press Act”. It was an Act made to prevent the frequent « abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Books and Pamphlets and for regulating of printing and printing presses ». The partisans of the liberty of press argue that this body would threaten the independence of the media from politicians. They remind people that, while the Licensing of the Press Act remained the law of the land, there were just a few newspapers that remained neutral and were not influenced by the king.

One other argument is that even if the phone hacking scandal has wounded many people, it would be false to say that the press has generally done more harm than good. Indeed it revealed to British people many abuses like the MPs’ expense scandal in 2009.

Finally, one can wonder if Cameron’s refusal is not due to a fear of a very powerful and influential press, which could seek revenge for press limitation.

How can David Cameron’s position be explained? What will tomorrow’s press be?

Although the Prime Minister himself asked for the inquiry, he is now the one who is most embarrassed. Indeed, in July 2011, he asked for an investigation after the phone-hacking scandal, involving Rupert Murdoch, but what the investigators found was unexpected: they discovered that Prime Minister David Cameron and the former editor of the British tabloid News of the World, Rebekah Brooks, knew each other well. Actually, several texts have been published about a horse road and a speech Cameron gave, giving clear evidence that the two of them were close. It illustrates the criticism according to which the press is much too close to politicians. This could be a reason why Cameron hesitated to implement Leveson’s suggestions.

Besides, this report is a major challenge for Cameron because what is at stake is the need to restore an institution which Great Britain abandoned 300 years ago. It would mean a step back for the Conservative Party and, in particular, for Cameron who claims to be a modernizer and who is more and more criticized in the coalition. Indeed, as further proof of its weakening, Nick Clegg first declared that he didn’t share Cameron’s positions. Furthermore, Ed Miliband also declared – and his opinion matched Clegg’s -that he would prefer “to set out a timetable for the implementation of a new regulatory body for the press that is independent of politicians and the industry but based on a position that has substantial support in Parliament”. In the end, the Prime Minister adopted this latest position as he declares in a video to the Guardian on the 4th of December.

In one of the country praising freedom as the most essential value, the press seems to have been given another chance to regulate itself independently. However, by focusing on press ethics, politicians may be missing an important part: web and digital press, which might well become a much bigger issue. Nowadays, with the era of social networks and news websites, it seems difficult to prevent news from leaking and spreading and even more to regulate their publication. Let’s hope they are going to figure out that soon enough to avoid being discredited …

Clémentine ROURE, Benjamin BAILLARD, Inès JOLY